My first roommate in Riyadh was a French teacher who once tutored an ex-political prisoner. The man was a retired lawyer who had belonged to a Marxist-Leninist network in the sixties, and had been part of a coup attempt against King Faisal. He had been tipped off right before his arrest and had escaped to Paris, where he studied law before coming back to Riyadh much later. Some of his comrades had less luck. Arrested on intelligence provided by US agents to the Saudi secret police, many of them were tortured or summarily executed. Some were even flown above the Empty Quarter and thrown alive out of helicopters.

These stories haunted me and led me to Turki al-Hamad’s trilogy, Specters in Deserted Alleys, set in the late sixties and early seventies. In the first volume, Adama, Hisham al-‘Abir, a high school student from Dammam, in the country’s oil province, joins the Saudi branch of the Baath socialist party.[1] In the second volume, Shumaisi, Hisham, now a college student in Riyadh, discovers alcohol, has an affair with a married woman, and is arrested for his past political activities.[2] The trilogy’s last volume, Karadib,[3] is the story of his confinement in a political prison. Brought to “a huge building shrouded in darkness” in the desert outside Jeddah, Hisham is questioned about his leftist leanings, and repeatedly tortured.

Karadib is the trilogy’s only volume that has not been translated into English. With its suspense and grit, it is also the most riveting. Chapter 11, whose translation The Common publishes here, is one of the climaxes of the book. Hisham sees his cell companions summoned in the middle of the night for interrogation sessions that leave them half-conscious for days. Evening after evening, as political discussions wear out and his comrades fall asleep, he is left alone with his fear of being that night’s victim. Out of despair, he exclaims one day, “God and the Devil are different sides of the same coin.” This sentence got Turki al-Hamad into trouble. After the book was published, incensed Islamists pronounced four fatwas against him, making Karadib his most famous text, and prompting comparisons with Salman Rushdie.

The book is important for yet another reason: it was one of the first Saudi fictions to shed light on state violence. With between 12,000 and 30,000 political prisoners, depending on the estimate, Saudi Arabia is as repressive an environment as Egypt or Syria. Saudi elites claim they protect the world’s first oil producer from “terrorism,” a conveniently hazy label. In the 1950s, unionists asking for better wages and protesting racial segregation were treated as national security threats. In the 1960s and 1970s, socialists and nationalists were jailed, tortured, and executed. The Islamists’ turn came in the 1990s and 2000s. Violence is not only used against political opponents. In police stations, religious police centers, and even schools, brutality, or the threat thereof, is common. By opening the door of the torture chamber, Karadib looks into one of the foundations of the Saudi status quo.

But repression often backfires. Families of political prisoners are prone to organize, protest, and get national and international attention. The Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo in Argentina marched against repression during the bleakest days of the military dictatorship. Saudi mothers, sisters, and relatives of political prisoners spoke out after a fire killed 67 inmates at the al-Ha’ir political jail on September 15, 2003. On October 14, 2003 and again on December 15, 2004, they marched to demand the liberation of all political prisoners. Mass arrests and live bullets did not deter them. During the 2011 Arab uprisings, mothers of political prisoners were with the Shiites among the rare Saudis to take to the streets.

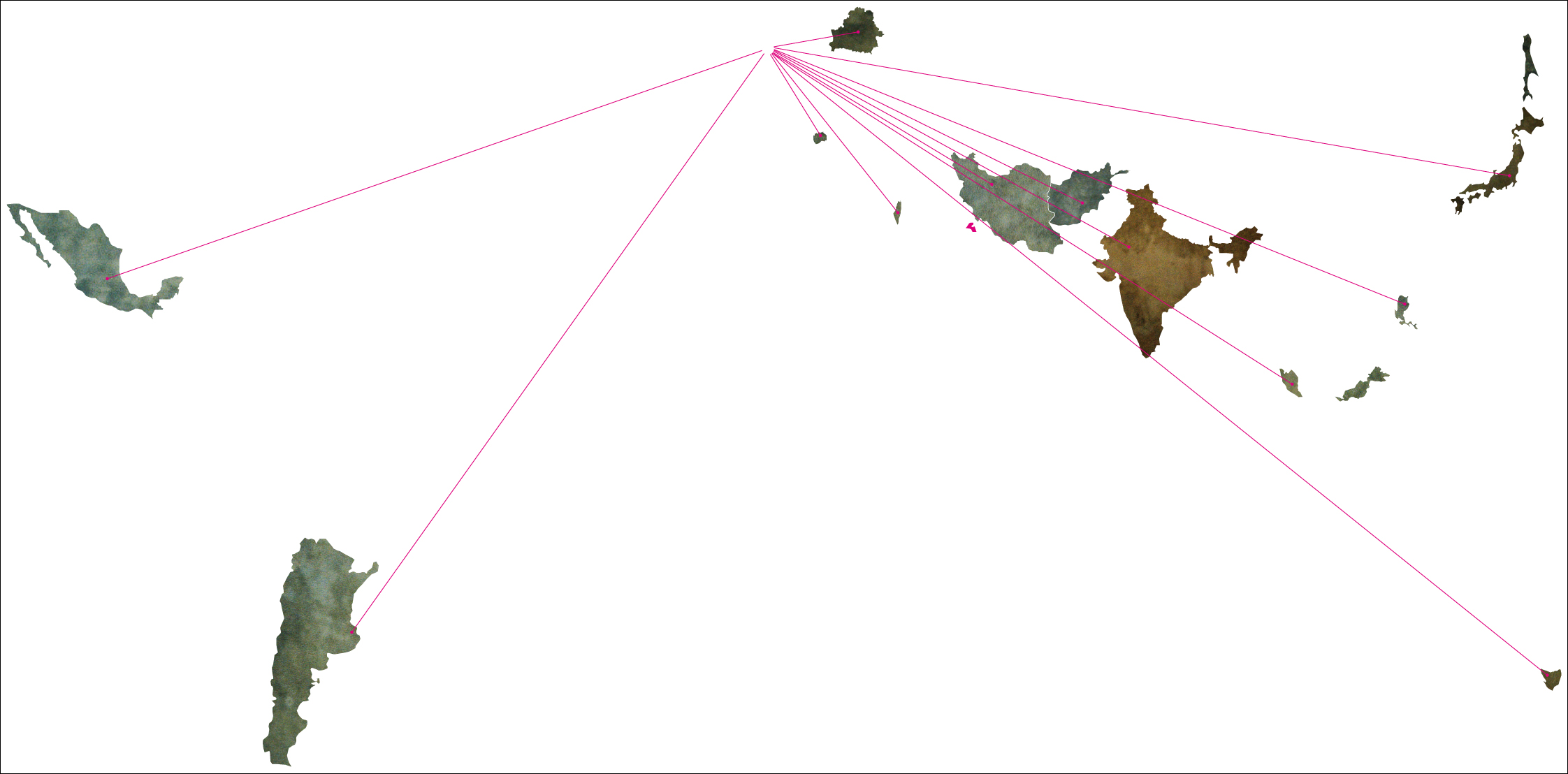

Turki al-Hamad is no stranger to state repression. On December 24, 2012, he was arrested by order of Interior minister Muhammad bin Nayef after a series of tweets that were judged offensive. He was released in June 2013. A year after his arrest, The Common publishes the climactic chapter of Karadib. The text was translated from Arabic into English by the NYU Abu Dhabi Translation Workshop, created in September 2012 to foster the reading and translation of modern Arabic literature on campus. Chapter 11 was translated by Philip Kennedy, associate professor of Middle East Studies at NYU, and Hasan Nabulsi, an undergraduate junior at NYU Abu Dhabi. It was collectively edited by the workshop’s members. This publication in two installments will hopefully bring attention to the fate of thousands of political prisoners detained across Saudi Arabia. We hope it also publicizes the booming Saudi novel and encourages translators and publishers to look into a fascinating literary scene.

[This introduction first appeared on The Common. To access the translation of Al-Karadib’s Chapter 11, click here.]

[1] Turki al-Hamad, Al-Adama (Beirut: Dar al-Saqi, 1995 – London: Saqi Books, 2003). - See more at: http://www.thecommononline.org/features/al-karadib-chapter-11-part-i#_ftn1

[2] Turki al-Hamad, Al-Shumaisi (Beirut: Dar al-Saqi, 1996 – London: Saqi Books, 2004).

[3] Turki al-Hamad, Al-Karadib (Beirut: Dar al-Saqi, 1998). - See more at: http://www.thecommononline.org/features/al-karadib-chapter-11-part-i#_ftn1

![[Cover of Turki al-Hamad`s Al-Karadib, by Dar al-Saqi]](https://kms.jadaliyya.com/Images/357x383xo/Screenshot2013-12-30at12.19.35PM.png)